Reprinted by permission from VoxDev

The spread of conditional cash transfer programmes in low- and middle-income countries has been described as perhaps the most remarkable innovation of recent decades in welfare programmes. These programmes provide regular cash transfers to poor families contingent on specific behaviours. These include school enrolment and regular attendance.

The programmes started in the late 1990s in Mexico and quickly became the public policy of choice to fight poverty and low enrolment. Today, more than 60 countries operate education conditional cash transfer programmes, often at a national scale.

There is plenty of evidence showing that conditional cash transfers boost enrolment. But evidence on their impacts on children’s learning is mixed. Explanations for the lack of learning gains relate to the short-term nature of the evaluations, which may not provide enough time for the learning effects to materialise.

In recent research, conducted in Morocco, we show that conditional cash transfers can constrain learning when no accompanying measures are taken by governments to account for increased enrolment. We found that the introduction of a programme can deteriorate school quality and thus constrain learning for children who enrol in school.

Conditional cash transfers in Morocco

We looked at a programme implemented at scale in Morocco. Known as Tayssir, it began operating in 2008 and quickly became the flagship education policy of a government strongly committed to reducing school dropout rates.

Earlier research showed that the pilot version of Tayssir had substantial positive effects on enrolment, but not on learning.

Following this evaluation, Tayssir was quickly scaled-up to reach annually up to 800,000 children in 434 municipalities. Because the allocation of transfers remained remarkably stable over time, the scaled-up version of Tayssir offers an ideal setup to study how conditional cash transfer programmes affect learning, with enough time for the effects to materialise.

Tayssir targeted all municipalities with a poverty rate above 30% and all households with children aged 6-15 within these municipalities.

To study the impacts of the programme, we used data from the information system of Morocco’s ministry of education.

In the first part of our analysis, we assessed Tayssir’s effects on dropout rates and checked for possible differences with the research done in 2015 on the pilot version of the scheme.

We confirmed that the grade-specific dropout rate decreased by 1.3 percentage points on average (41% of the sample mean). This is equivalent to an increase in enrolment of about 9 percentage points by the end of grade 6.

We found a greater decrease for girls: 1.8 percentage points, or 50% of the sample mean.

Remarkably, these estimates were in line with those on the pilot, despite the nationwide expansion of the programme and the ten-fold increase in the number of beneficiaries.

The impact on quality

The reduction of the dropout rates induced by Tayssir may have affected both class size and class composition by retaining lower-ability students. This could potentially lead to negative effects on learning outcomes through peer effects and less effective teaching practices.

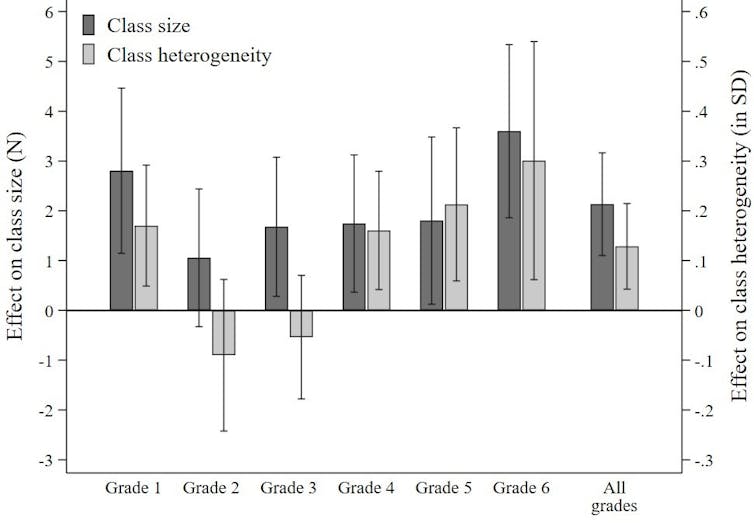

Our estimates show that class size in targeted areas increased by 3.6 students by the end of primary school, equivalent to 12% of the sample mean.

Variation in class composition increased by 0.30 standard deviations (SD) by the end of primary school.

Figure 1 shows that these effects are stronger in higher grades. This suggests that the reduction in dropout rates accumulated over time and progressively overburdened school resources. Large effects in grade 1 likely reflect the fact that children in targeted municipalities started school earlier – possibly to benefit from the transfers – and repeated grade 1 more often.

Figure 1: Effect of Tayssir on class size and heterogeneity

Notes: Each bar reports the coefficient estimate of the local average treatment effects of Tayssir. The dependent variables are class size (number of students per class) and class heterogeneity (standard deviation of the GPAs within a class). 95% confidence intervals are reported.

Larger class sizes and increased differences in class composition had negative impacts on children’s test scores.

In the final part of our analysis, we looked at the effects on test scores at the end of primary school exam. We found that Tayssir had negative effects on test scores. We estimated that the programme reduced test scores by 0.12 standard deviation for the full sample.

What needs to be done

Our insights should not be interpreted as evidence that policymakers should not pursue conditional cash transfer programmes. Such programmes, including the one we study, have proven particularly effective at increasing access to education, which is a crucial first step to enhance learning.

These programmes also have many other benefits. These include delayed marriage and childbearing for adolescent girls.

However, our results, together with evidence showing alarmingly low literacy and numeracy levels among students in low- and middle-income countries, indicate that the attendance gains from the programmes alone are unlikely to equip students with the foundational skills they need to thrive.

In fact, our results show that conditional cash transfer programmes can have adverse effects on learning when schools lack the necessary resources to accommodate the influx of new students. Such insights may be particularly relevant for other interventions aiming to increase school attendance without complementary investments in school capacity.

Recent decades have seen a surge in evaluations focusing on the learning effects of education interventions in low- and middle-income countries. Although there is no silver bullet to raise learning, some “great buys” emerged from the 2023 report of the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel:

-

providing information on the benefits, costs and quality of education;

-

supporting teachers with structured pedagogy;

-

pedagogical interventions that tailor teaching to student learning.

In Morocco, where our study takes place, other scholars have demonstrated that an intervention combining two of these three “great buys” – targeted instruction based on learning level and structured pedagogy – yields large gains in learning.