Smart watches can be used for data collection among other functions. PHOTO/Ella Maru

KEY FINDINGS

Data Collection: The study analyzed smart-watch data from over 5,000 adolescents, focusing on metrics such as heart rate, sleep quality, and physical activity levels.

Digital Phenotypes: Researchers introduced the concept of “digital phenotypes,” which refers to observable traits derived from digital data.

Genetic Associations: The study identified 37 genes associated with ADHD, demonstrating how smart-watch data could help uncover genetic links to psychiatric illnesses.

Clinical Implications: The findings suggest that using smart-watches could revolutionize traditional diagnostic methods in psychiatry.

Future Applications: While the study primarily focused on Attention-deficit, hyperactivity disorders (ADHD) and anxiety, researchers believe this methodology could extend to other psychiatric and neurological disorders, enhancing understanding of mental health across various conditions.

By PATRICK MAYOYO

Smart-watches that can collect physical and physiological data on users could be potentially interesting tools in biomedicine to gain a better understanding of brain diseases and behavioural disorders and possible driver mutations related to these pathologies.

This is stated in a study published in the journal Cell, and led by the co-author Mark Gerstein, from Yale University (United States). The study includes the participation of Professor Diego Garrido Martín, from the Department of Genetics, Microbiology and Statistics of the Faculty of Biology at the University of Barcelona.

Smart watches can be also be utilized in genetic associations research. PHOTO/UGC.

Using smart watch data from more than 5,000 adolescents, the research team could train artificial intelligence models to predict whether individuals had different psychiatric illnesses and found genes associated with these illnesses. The results suggest that these wearable sensors may enable a much more detailed understanding and treatment of psychiatric illnesses.

“In traditional psychiatry, a doctor will assess your symptoms and you’ll either be diagnosed with an illness or won’t”, says Professor Mark Gerstein, an expert in biochemistry, computer science, statistics and data science.

“But in this study, we focused on processing the wearable data in a way that could both be leveraged to predict illnesses more comprehensively, and to better connect them to underlying genetic factors”.

Detecting illnesses in such a quantitative way is difficult. But wearable sensors, which collect data continuously over time, may be the answer. For the new study, the team used data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, the largest long-term assessment of brain development and child health in the United States.

The data used in the study — collected from by smart watches worn by adolescents aged 9-14 — included measurements of heart rate, calorie expenditure, physical activity intensity, step count, sleep level and sleep intensity.

“When processed correctly, smart watch data can be used as a ‘digital phenotype’”, says researcher Jason Liu, a member of Gerstein’s lab and co-lead author of the study.

The researchers propose using the term digital phenotype to describe traits that can be measured and tracked with digital tools such as smart-watches.

“One advantage of doing this is that we can use the digital phenotype almost as a diagnostic tool or a biomarker, and also bridge the gap between disease and genetics”, Liu adds.

Smart watches can be used for “digital phenotypes,” which refers to observable traits derived from digital data. PHOTO/UGC.

To that end, the researchers also developed a methodology for obtaining the massive amount of smart watch data and converting the raw data into information that could be used to train an AI model, “a new problem to solve in the research world which is technically challenging”, according to Gerstein.

The team found that heart rate was the most important measure for predicting Attention-deficit, hyperactivity disorders (ADHD), while sleep quality and stage (the different cycles a body goes through during sleep) were more important for identifying anxiety.

“These findings suggest that smart watch data can provide us with information about how physical and behavioural temporal patterns relate to different psychiatric illnesses”, Gerstein said.

Moreover, the data could also help differentiate between different subtypes of the disease. “For example, within ADHD there are different forms”, said Beatrice Borsari, a postdoctoral associate at Gerstein’s lab and co-lead author of the study.

“Maybe we can extend this work to help distinguish between forms of inattention and hyperactivity, which typically respond to different pharmacological treatments”.

Having seen that the digital phenotype could be used to predict psychiatric illnesses, the team investigated whether it could also help identify underlying genetic factors, using a series of multivariate statistical tools developed thanks to the scientific contribution of the University of Barcelona.

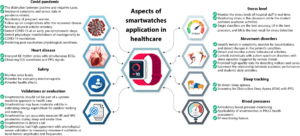

INFOGRAPHIC/UGC

“Our methodology has made it possible, for the first time, to simultaneously analyse the relationship between genetics and the different measures provided by smart watches”, says Diego Garrido Martín, UB professor and co-author of the study.

When they examined whether genetic mutations affected the smart watch data differently in healthy individuals than in those with ADHD, they were able to identify 37 genes associated with ADHD.

But when they ran a similar analysis to determine whether particular genes were associated with an ADHD diagnosis, they found none. This discovery highlights the added value of using continuous smart watch data, says the team.

The findings link psychiatric illnesses, digital phenotypes and genotypes and show how wearable sensors can provide a deeper understanding of psychiatric diseases.

“This method holds great promise for addressing long-standing challenges in psychiatry and may ultimately reshape the way we understand the genetics and symptom structure of psychiatric disorders”, said Walter Roberts, assistant professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine and co-senior author of the study.

Although the study focused on ADHD and anxiety, the researchers expect the approach to be widely applicable. For example, it may be useful for understanding neurological diseases or neuro-degeneration.

In addition, they hope that their findings may serve as inspiration to move beyond traditional clinical diagnostics and adopt quantitative behavioural measurements that may be of greater use in identifying genetic biomarkers.