South Africa’s new Expropriation Act, which was signed into law by President Cyril Ramaphosa in January 2025, has been at the centre of a political storm set off by the new US administration under President Donald Trump.

The Expropriation Act is not entirely new. It mainly updates the existing legislation from 1975 to align it with the constitution of democratic South Africa. But some have misinterpreted it as making room for land grabs by the state. That’s not what it does in reality. Property rights remain intact in South Africa.

Hot on the heels of this furore has been a notice from the minister of land reform and rural development, Mzwanele Nyhontso, that the government is embarking on a new bit of legislation, the “Equitable Access to Land Bill”.

There have been discussions over the last 10 years about developing a land reform framework bill or land redistribution bill. The main idea is to foster conditions that enable citizens to get access to land equitably. Land ownership was heavily skewed towards white people under apartheid.

The parliamentary committee heard from the minister on 20 February 2025 that there were gaps between the white paper on South African land policy and existing legislation. The bill seeks to close the gaps. It would provide for, among other things, principles for access to land, access to land by the state and citizens, the identification and selection of beneficiaries, applications and records for land allocations, a register of agricultural land, notification of present land ownership, land ownership ceilings, a land tribunal and regulations.

Based on our years of work on land reform and agricultural policy it’s unclear to us why such a bill is necessary. We believe there are two reasons a new law would be superfluous. Firstly, South Africa already has roughly 16 laws that address the issue of land. Secondly, policymakers tend to ignore the facts on land reform progress.

It is hard not to view the obsession with new legislation by every new minister as a distraction from the core issues. The minister should be focusing on distributing the land the government has acquired to black farmers and give them title deeds. This will be sufficient effort to build an inclusive agricultural sector, while continuing with existing programmes of land acquisition from the open market.

There are also other areas that should be reformed that would make a difference. These include making more finance available to aspirant black farmers and fixing the deeds office to reduce land registration times.

What’s in place

There should be no need for new legislation if one considers all the different pieces of legislation and government programmes that are already aimed at a more equitable distribution of land. There are at least 16 laws related to farm land and the restitution and redistribution process. These include:

-

Preservation and Development of Agricultural Land Act, signed into

law in January 2025 -

State Land Disposal Act, 1961 (Act No. 48 of 1961)

-

Deeds Registries Act, 1937 (Act No. 47 of 1937)

-

Land Reform: Provision of Land and Assistance Act, 1993 (Act No. 126 of

1993) -

Restitution of Land Rights Act, 1994 (Act No. 22 of 1994)

-

Communal Property Associations Act, 1996 (Act No. 28 of 1996)

-

Land Reform (Labour Tenants) Act, 1996 (Act No. 3 of 1996)

-

Protection of Informal Land Rights Act, 1996 (Act No. 31 of 1996)

-

Extension of Security of Tenure Act, 1997 (Act No. 62 of 1997).

In addition, South African policymakers tend to ignore the facts on land reform progress.

As we have argued before, the mix of government programmes to restore land rights and redistribute land has already addressed 25% of the total area of farm land defined and registered by formal title deeds. This means that 19.5 million hectares of the 77.5 million hectares of South Africa’s farm land have been affected by the government land reform programmes.

There is an important nuance here: 2.5 million hectares have been acquired by the state and are now owned by the State Land Holding Account.

Calls for the state to redistribute this land to black farmers have been falling on deaf ears, and black farmers continue to despair.

The government has been slow to distribute the land it has acquired. This shows that the problem of South Africa’s land reform is not only about acquisition but also the distribution of land with title deeds to beneficiaries.

Included in the total of 19.5 million hectares are private purchases of farm land by black South Africans. We estimate a total of 2.4 million hectares have been acquired in this way up to the end of 2024.

These individuals used their own funds or borrowed funds to acquire the land without using any of the state programmes.

Some answers

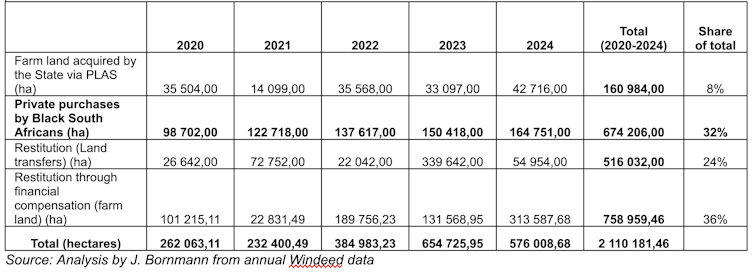

We have always argued that the private transactions where no bureaucrats are involved happen much quicker than any government programmes. The table below shows the relevant statistics for the last four years and confirms the argument.

The table shows that over the last four years private land transactions (that is without any involvement of bureaucrats) have contributed 32% to the total area of farmland transferred or restituted. The land claims process, in terms of the Restitution of Land Rights Act, has made the biggest contribution of 60% (with 36% of land restituted via financial compensation and 24% of land transferred to claimants). Other government land reform programmes made a very small contribution.

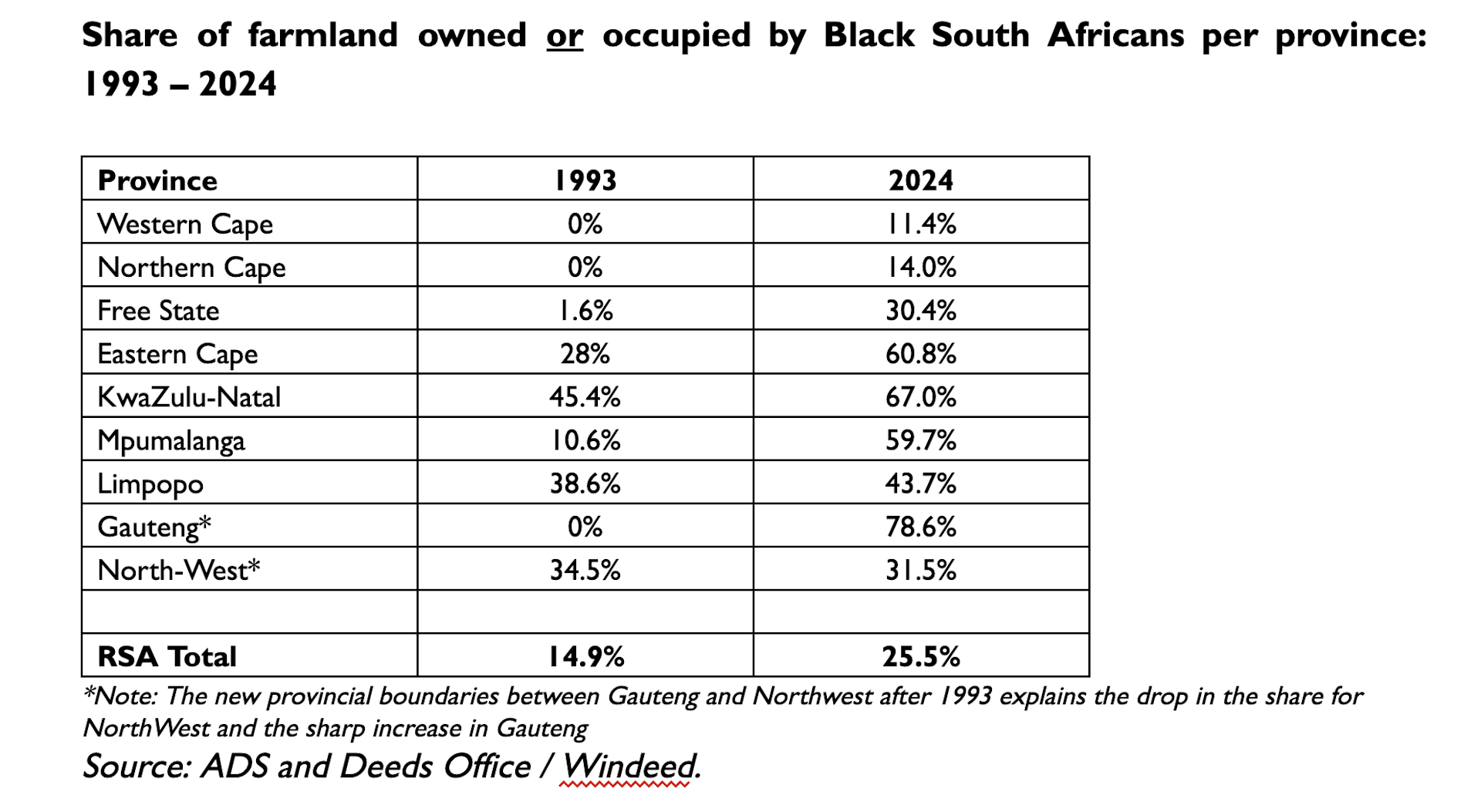

Do we have more equitable access to farm land (or rural land) after 30 years of democracy? To answer this question, we need to take into account the occupation of farm land under traditional tenure arrangements and occupation on land owned by the state, including the South African Development Trust land as well as the land recently acquired by the state under the Proactive Land Acquisition Strategy programme, which is in most cases leased to black beneficiaries for short terms.

In addition, we account for the land redistribution programme and the land transferred back to land claimants. The numbers below provide an interesting picture of black ownership of rural land in South Africa. In some provinces, equitable access has shown remarkable progress, as shown in the table below.

Instead of a new law, this is what’s needed

First, access to affordable and preferential finance for land acquisition by black farmers would make an important contribution to equitable access. But no new law is needed to enable this. The answer lies in changing the way the Land Bank is funded so that it can provide affordable finance to aspirant farmers. This would be a game changer.

Secondly, government should act on the president’s proposal to establish the Land Reform Agency, release more unused state land for agricultural use and change the regulations to facilitate private land donations to beneficiaries.

Thirdly, fix the processes and data issues in the deeds office, which could reduce the time and costs to register property transfers.